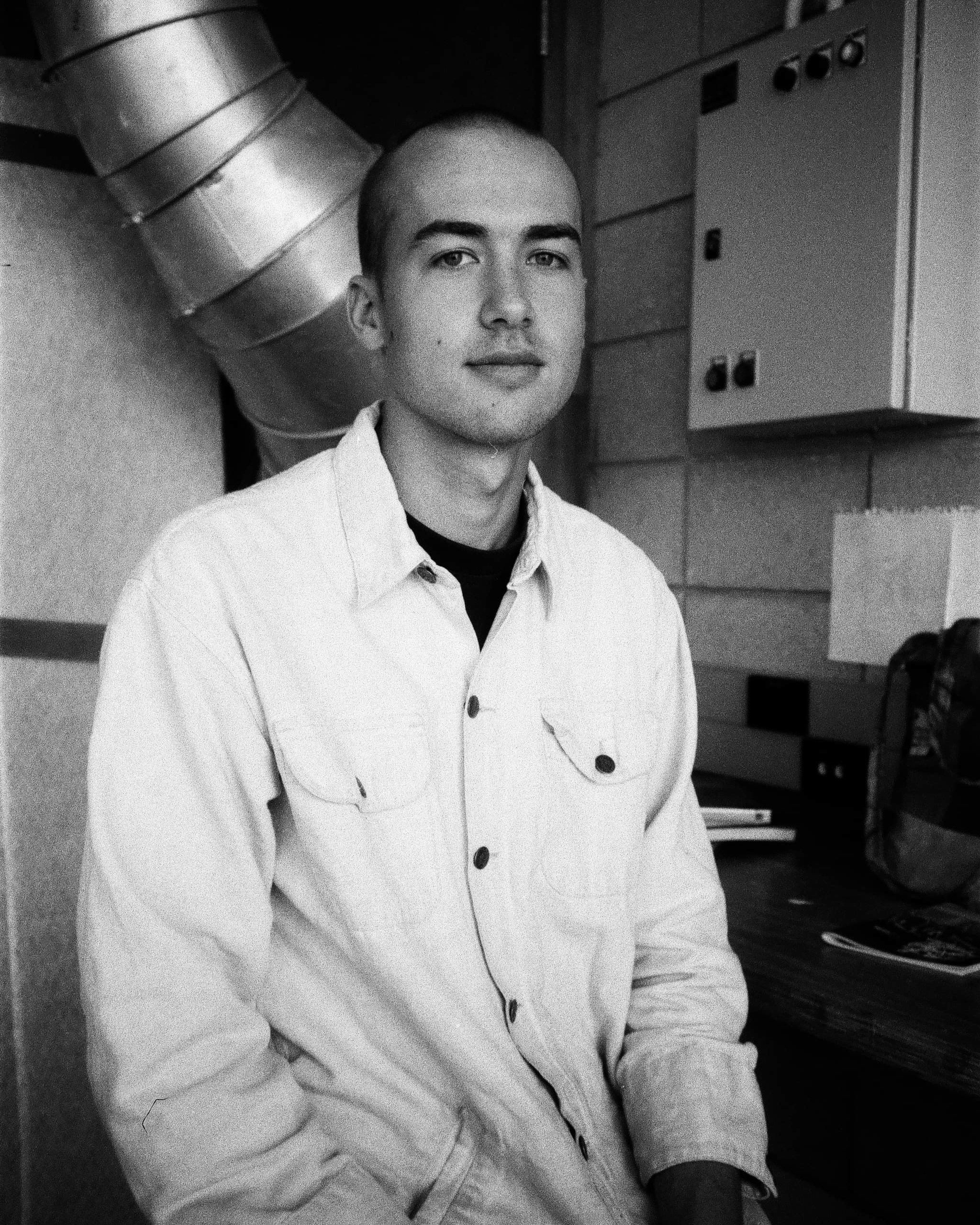

SummaryHarrison Freeth is an artist of German-Tongan, Sāmoan, and Scottish heritage, born in Ōtepoti and based in Tāmaki Makaurau.

Working across sculpture, installation, and drawing, his process-based practice is guided by curiosity, materiality, and open-ended learning. Freeth explores how elements of children’s play such as model-making, role-play, repetition, and symbolism extend into adult life as tools for navigating uncertainty and complexity.

Through themes of identity and belonging, his work reflects on how we come to understand the world; not by seeking answers, but by asking more questions. In this space of inquiry, the personal begins to blur with the collective, revealing how individual experiences both shape and are shaped by a larger shared history.

Freeth studied at Dunedin School of Art, graduating with a Bachelor of Visual Arts and a major in sculpture. His works are held in the collections of Canterbury Museum, Otago Polytechnic and the Wrightsman House.

Over the course of my Fale-ship Residency, I spent three months staring at the face of my own history in the form of a 1910s Grey Lynn villa, researching, making, and listening to what this weatherboarded facade had to tell me.

From the 1960s until her death in the 1980s, this home belonged to my Great Nana, Flora Guttenbeil, and it was only recently that I learned of its address. As a part of the many families who migrated to Aotearoa from the islands during the mid-20th century, Flora’s home would become a part of a growing hub of Polynesian settlement. For these migrating families, the faces of their new homes would take on new kupesi in the shifting patterns of belonging and identity found in Aotearoa. Kupesi, in Tongan, commonly translated as motif or pattern, can also be used to refer to the genealogical patterns visible in a face. To understand how this face of history and its people changed for this generation, I began researching the conditions that led to this wave of migration.

With the end of World War II, rapidly developing industrial and agricultural sectors in Aotearoa had the New Zealand government actively recruiting Pacific Island labourers. By the 1960s formal work-permit schemes were introduced bringing workers mainly from Fiji, Tonga, and Sāmoa. In 1945, at the end of World War II, the New Zealand Government census counted 2,200 people identifying as ‘Pacific’ across Aotearoa. By the mid-1980s this number sat closer to 150,000.

Entering through the Waitematā harbour on ships like the TSMV Matua, the majority of that growing population found their new homes not far from the port. The greater Ponsonby region was ideal for most, offering affordable rent, convenient transport options, proximity to the city, and the Waitematā Harbour, which facilitated connections back home through freight and transport. Seeing these numbers laid out showed a dramatic shift over a single generation and cemented the scale to which this community would reshape Aotearoa and christen Tāmaki Makaurau as the colloquially referred ‘Capital of Polynesia’.

However, Aotearoa's colonial government subjected this thriving community to malevolent, systematic and culturally racist persecution. Police brutality, dodgy landlords, and racial prejudices birthed social justice movements such as the Polynesian Panthers, who became a voice for their communities. While the community battled for the right to exist peacefully, dawn raids made way for more sinister, systematic tactics of pushing Pasifika people out of the area. Work opportunities moving to the city’s outer limits, the rising costs of living, and wealthy investors purchasing property close to the city created the perfect climate for gentrification. In 1971, 42% of people living in the greater Ponsonby region were of Māori and/or Moana Oceanic descent, and by 2023, this combined percentage was less than half, at 18.7%.

Numbers can tell a story. Alongside historical analysis, they revealed an overarching narrative that tells a tale of a community thriving and then dispersing. This research grounded my Great Nana’s villa within a broader narrative, painting the mise en scène of an era I’m unable to experience in time and space. Yet experience has its orators, and the lived experience of this time and space still resides in my own family and community. In speaking to people who lived through this period, I watch history’s face grow a mouth and speak to me. The seemingly linear arc from World War II to today revealed itself as multiple, interconnected pieces in a constantly shifting puzzle.

Beginning the Fale-ship Residency, it was never my intention to find a singular image that these puzzle pieces might represent. For me, the question of connection lay within what it means to inherit a cultural history you did not experience. My Great Nana’s home on Richmond Road was a place of gathering, connection, and knowledge for our family. When she died in the late 80s, the home, which once served as a family hub, was sold. The selling of this house and the subsequent dispersal of the family ritual to gather there has come to mean, for me, the point of dispersal in the ritual and cultural connections to the Moana.

Like many descendants of families who settled in the greater Ponsonby region, I no longer have access to the homes where they once lived. At first, I saw the villa’s facade as a barrier, a face with no door open to me. But the longer I looked, the more I began to see the kupesi of my family and community embedded in its European architecture. The weatherboard patterns that sheltered Pasifika families, windows that framed new kinds of domestic life, the verandas where different cultural practices merged, and the fence where ‘Fēfē Hake Masi’i’ was heard as opposed to ‘How are you?’.

While I had been trying to learn my history, it was always present in the kupesi of my family, which I carry through me today. When she died, my Great Nana was standing over the laundry tub in her Richmond Road home. Her teeth fell from her mouth into the tub, and she fell back into a family member’s arms, her smile the last thing she left in this world. As my Fale-ship residency concludes, this is the story that sits with me the most. Three months prior, I stared at the facade of an old Grey-Lynn villa, wondering about what stories it might tell me if it had a mouth to speak. Now in an ode to the oral stories that have come from those who once lived there, I cast my own teeth in bronze, creating a permanent record of my own smile.

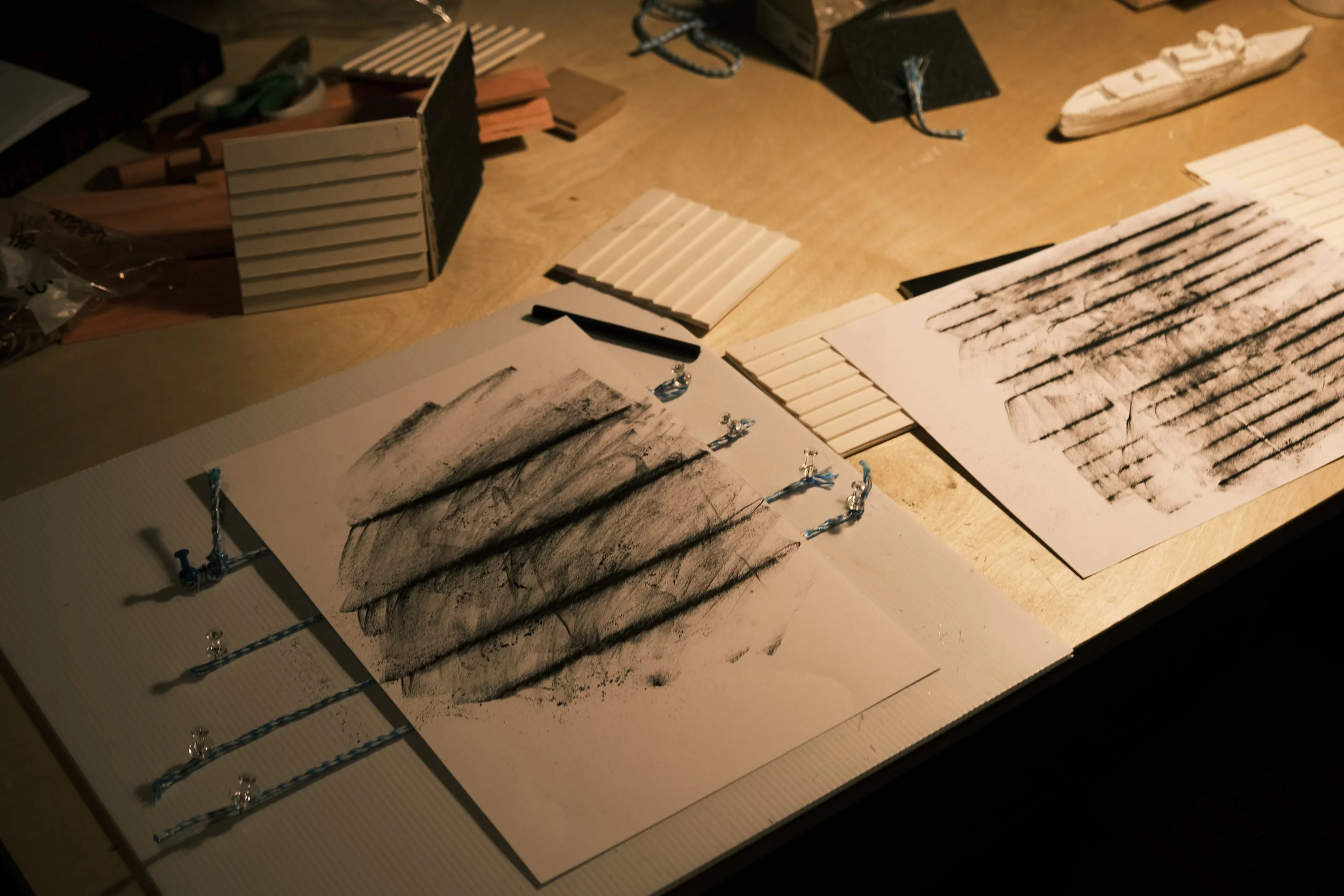

This has been one of the products of months of material experimentation. In examining the ways material relationships can bring these stories to life, I explored soap for its domestic intimacy, modular tiles that can be rearranged like puzzle pieces, and real estate signs as economic doors. In doing this, I was searching for ways to make the invisible connections visible, modeling what I realised was no longer a physical space but a relational space, connected to the dispersed parts of a familial and cultural history.

Concluding my residency, I have come to see that for many descendants of displaced communities, the kupesi of connection remains, waiting to be discovered through new forms of engagement with inherited histories, but always visible in the shape of a smile.